Film Review: “Passing” Is a Meditation on Race, Class, and Black Womanhood

Rebecca Hall is one of those rare filmmakers who can draw inspiration from her life and create a great work of art. In an essay she wrote for Vogue, Hall recalled her confusion growing up in the English countryside. Though she lived a highly privileged and creatively fulfilling life, her family’s background was shrouded in mystery. Her parents are world-famous opera singer Maria Ewing and Royal Shakespeare Company founder Peter Hall. Hall’s father is a white man from Suffolk, and her mother is a biracial woman from Detroit. But the only thing she knew about her extended family was that her grandfather from her mother’s side passed as a white man.

Thanks to some digging, Hall discovered that her grandfather passed while he worked as an engineer at McLouth Steel during the 1950s. And like her mother, he dabbled in the arts. But what she did not understand was why he passed. It was not until she read Passing, a book by Nella Larsen, that Hall finally got some answers. Set during the Harlem Renaissance, Passing follows the reunion of two childhood friends. Both biracial women with fair skin, one thrives in the Black community while the other passes as white.

As she read the novel, the actor turned filmmaker learned why people like her grandfather passed, the great lengths they took to keep their ancestry a secret, and the guilt they felt as they deceived others. Touched and inspired, Hall immediately wrote her first feature adaptation based on the tragic story that is now available on Netflix. Beautifully rendered but heart wrenching to watch, Passing is a timely meditation on race, class, and Black womanhood in 1920s Harlem.

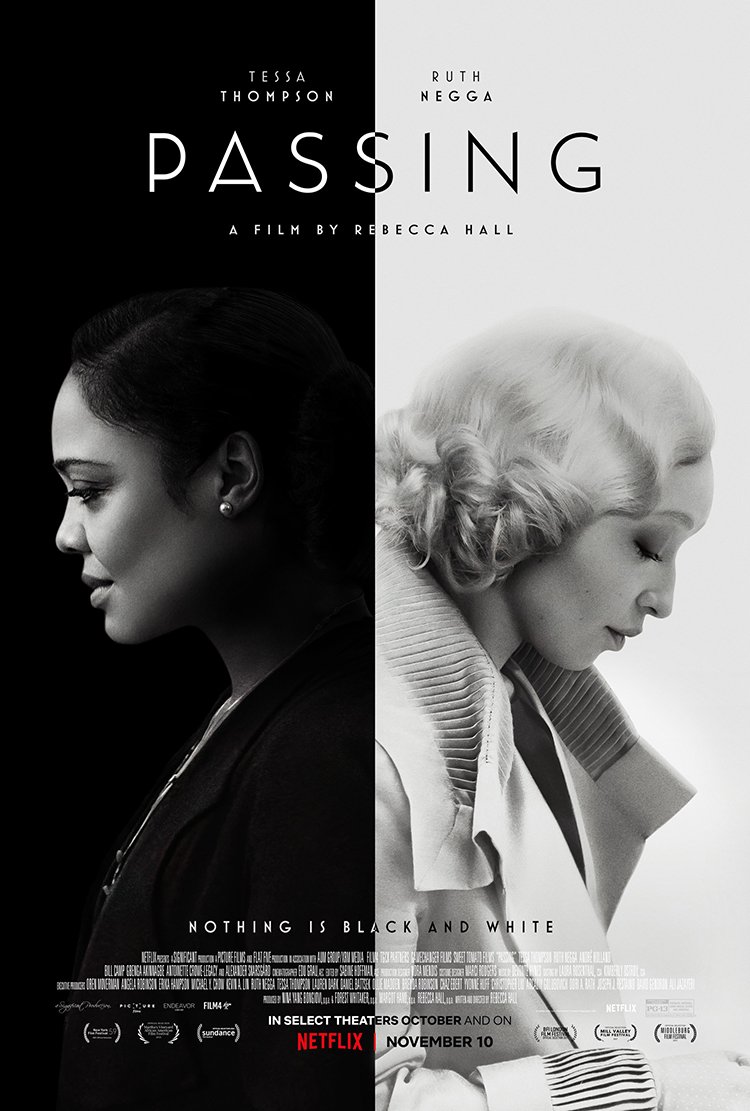

Passing begins with Irene (Tessa Thompson) as she shops for gifts for her sons in New York City. Worried that a white person may notice her, she obscures her face and natural hair under a hat to conceal that she is a light-skinned biracial woman. After purchasing several toys, Irene heads to the Drayton hotel to cool off from the summer heat. Once there, she runs into Clare (Ruth Negga), a childhood friend, who is passing as a white woman. Nervous, Irene attempts to leave the hotel, but Clare intercepts her. With nowhere to run, she reluctantly accepts an invitation for fancy tea and cakes in Clare’s hotel room, where she meets her friend’s racist white husband, John (Alexander Skarsgård). The meeting is, ahem, awkward.

Irene returns to her life in Harlem, where her Black husband Brian (André Holland) and two young sons await. Though the screen is void of color, her life is not. Her marriage to Brian is trying but not broken, her sons love her dearly, and the Black community in Harlem respects her. However, Irene’s world begins to crack when she receives multiple letters from Clare. Though she tries to ignore the woman, Clare eventually finds a way to imbed herself into every aspect of Irene’s life.

Passing is the type of story that will immediately start a conversation. For one thing, there is a long history of people passing as a different race in America. For every oddity like Rachel Dolezal and Jessica Krug, there is Beverly and Harriet Hemings, the alleged children of Thomas Jefferson and his slave mistress Sally Hemings. These pair of siblings passed into white society after Jefferson released them from his plantation. It is easy to judge Hall’s grandfather, the Hemings family, and Clare for passing, but they had to do it to survive a society that treated them less than human. And although these people managed to elevate their standing in society, they also lost many things, such as their family, safety, and sense of community.

Hall delicately depicts the emotional toll of passing as white through the lives of Clare and Irene. This is evident when Clare invites Irene to chat in her hotel room. Though the two women enjoy their unexpected reunion (for the most part), the mood changes when John returns from his business meeting. As Irene evades eye contact while talking to John, Hall keeps the camera close on the character’s face to emphasize her fear. And although Clare is comfortable standing behind her man, her smiles and laughter barely hides the pain she feels as John explains why he calls his wife “Nig.” This scene, which is beautifully rendered in black and white by cinematographer Eduard Grau, shows the mental and physical work Clare and Irene must do to make their act convincing to white people.

Just as Hall captures what it is like passing as white through her camera, Tessa Thompson and Ruth Negga masterfully show the nuance of passing through their performances. Like many seasoned actors in their field, they know how to make their nonverbal actions speak louder than their verbal ones. Like when Irene asks Clare if her husband knows she is biracial, the woman responds by bashfully shaking her head. Perhaps indicating that she is ashamed – and a little giddy – that she got away with passing as white woman for so long. The performers are also good at showing the different ways they pass as white women. While Irene covers her Blackness by hiding her natural in tight curls and a hat, Clare lives her life openly with her bleached blonde hair and charismatic demeanor.

André Holland and Alexander Skarsgård also hold their weight against Thompson and Negga. Holland, who’s past work includes High Flying Bird and The Eddy, gives a layered performance as Irene’s unsatisfied husband. His conversation with Tessa at the dining room table showcases the actor’s abilities as a performer. The way they talk over each other as they argue about racism, their marriage, and of course, Clare feels painfully real. Skarsgård also gives one of the best (and scariest) Racist White Person in a Black Film performance since Allison Williams in Get Out. Though The Big Little Lies is only in a few scenes, you will feel his domineering presence everywhere.

Like a talented jazz band in a smokey night club, Passing manages to show the delicate balance of passing as a white woman in 1920s Harlem. Though the film can get melodramatic at times, the first-time feature director/writer/producer proves that she can craft a compelling period drama that is worth viewing.